Frequently asked questions

While seahorses appear to be very different from other fishes in the sea, they are fish nonetheless. They belong to the same class as all other bony fish (Actinopterygii), such as salmon or tuna. If one stretches a seahorse and lies it stretched out on its stomach, it is easy to see that they really are fish. Seahorses are members of the family Syngnathidae from the Greek words syn, meaning together or fused, and gnathus, meaning jaws. They share this family with fish like the pipefish. Seahorses alone belong to the genus Hippocampus, from the Greek words for horse (hippos) and sea monster (campus).

The number of actual seahorse species is a point of conflict for scientists, with the relationships between the various species not fully resolved. Project Seahorse currently recognizes 46 species. However, this number is likely to change with further taxonomic research.

Seahorses appear to be the fusion of various different animals. The have a horse-like head, monkey-like tail, and kangaroo-like pouch. In fact, even their eyes can be likened to those of a chameleon in that they move independently of each other and in all directions. Instead of scales, seahorses have thin skin stretched over a series of bony plates that are visible as rings around the trunk. Some species also have spines, bony bumps, or skin filaments protruding from these bony rings.

A group of spines on the top of the head is referred to as the coronet, and looks like a crown. Seahorses are masters of camouflage, changing colour and growing skin filaments to blend in with their surroundings. Short-term colour changes may also occur during courtship displays and daily greetings. Male and female seahorses can be told apart by the presence of a brood pouch on the male.

Seahorse heights are measured from the tip of the tail to the top of the coronet. Seahorse sizes vary with species ranging from the large Australian big-bellied seahorse (30 cm or more in height) to a tiny pygmy seahorse (less than 2 cm high). Their weights vary with age and reproductive stage.

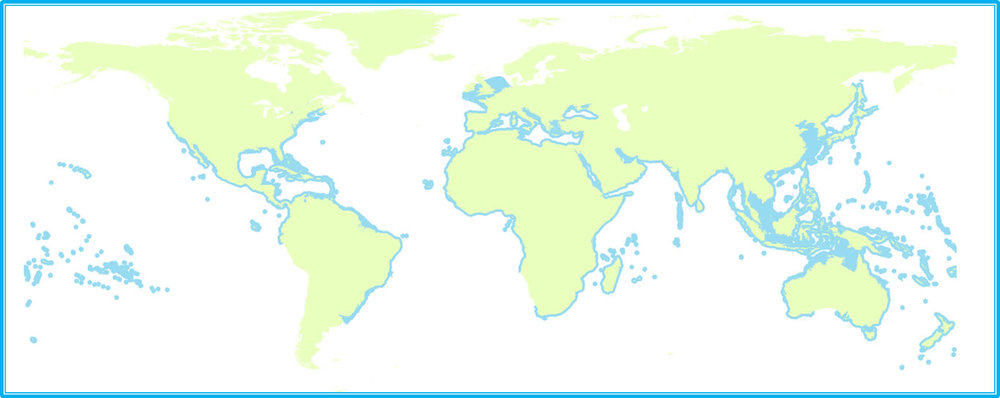

All seahorses are marine species, generally living among seagrass beds, mangrove roots, and coral reefs, in shallow temperate and tropical waters. Some species can also be found in estuaries, tolerating wide ranges in salinity. Seahorses range roughly from 50 degrees north to 50 degrees south latitude, with most species occurring in the West Atlantic and the IndoPacific region (see map - blue shading denotes where seahorses are found. Source: Riley Pollom/Project Seahorse). Habitat degradation is a real threat to seahorse populations as they mainly inhabit shallow, coastal areas which are highly influenced by human activities.

The natural lifespans of seahorses are virtually unknown, with most estimates coming from captive observations. Known lifespans for seahorse species range from about one year in the smallest species to an average of three to five years for the larger species.

Seahorses have no stomach or teeth. Instead, they suck their prey in through a tubular snout (a fused jaw) and pass it through an inefficient digestive system. Seahorses are voracious predators, relying entirely on live, moving food. They are opportunistic predators, waiting until prey come close enough and then sucking them quickly out of the water with their long snouts. Each eye moves independently, allowing the seahorse to maximize its search area. They will ingest anything small enough to fit into the mouth (mostly small crustaceans such as amphipods, but also fish fry and other invertebrates).

Adult seahorses are presumed to have few predators due to excellent camouflage, a sedentary lifestyle, and unappetizing bony plates and spines. They have been found in the stomachs of large pelagic fishes such as tuna and dorado, however, and are also eaten by skates and rays, penguins and other water birds. A seahorse has even appeared in the stomach of a loggerhead sea turtle. Crabs may be among the most threatening predators with damaged tails indicating a narrow escape. Young seahorses are the most vulnerable to being eaten by other fish. For some populations of seahorses human beings are the greatest predator.

Adult seahorses have retained only a subset of the fins found in most other adult fish, the dorsal fin, a tiny anal fin, and two tiny pectoral fins on either side of the body. They swim using the propulsive force of the quickly oscillating dorsal fin, and use the pectoral fins on either side of the body for steering and stability. They are more adapted to maneuverability than speed, and therefore rely more on camouflage to avoid detection from predators than speed for escape.

A common question is if the males get pregnant, why aren’t they called females? The reason is that like all other male and female animals, it is the male seahorse that provides the sperm and the female seahorse that provides the eggs. The female deposits her eggs in the male’s pouch, after which the male fertilizes them. The pouch acts like a womb, providing nutrients and oxygen to the developing animals, while removing wastes. The pouch also acts like an osmotic adaptation chamber, with the internal fluid changing slowly over the course of the pregnancy from similar to body fluids to more like the surrounding seawater. This helps reduce the stress of the offspring at birth.

Most species of seahorse studied in the wild do appear to be monogamous, remaining faithful to one partner for the duration of the breeding season and perhaps even over several seasons. There is evidence that some species are not monogamous (in other words, polygamous), especially when put into a captive environment. Where they are monogamous, the pair-bonds are reinforced by daily greetings, in which the female and male change colour and promenade and pirouette together. This dance lasts several minutes, and then the pair separates for the rest of the day.

Pregnancy lasts about two weeks to one month, the length decreasing with increasing temperature. At the end of gestation the male goes into labour (usually at night), pumping and thrusting for hours to release his brood. Young are miniature adult seahorses, independent from birth, and receive no further parental care. Newborns of most species measure between 7 and 12 mm. Most males give birth to around 100-200 babies, however the smaller species can have a few as five, and one Hippocampus reidi male gave birth to 1572 young!

Seahorse behaviour and ecology make them very vulnerable to over-exploitation. In the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, 11 of the 35 seahorse species that have been assessed so far are listed as Vulnerable, with one listed as Endangered, one as Near Threatened and two as Least Concern. The other 20 are listed as Data Deficient demonstrating the lack of knowledge of seahorse biology, and the urgent need for more research. The Red List also indicates the need for the development of conservation programs. For more information about the IUCN Red List, see www.iucnredlist.org.

Seahorses are exploited for use as traditional medicines, aquarium fishes, curios (souvenirs), and tonic foods. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is the largest direct market for seahorses, but they are also used in other traditional medicines. Many seahorses in aquariums are wild-caught, while dead seahorses are incorporated into jewelry, key chains, paper weights, and other crafts. They are also threatened by the destruction of their coral reef, mangrove, seagrass, and estuarine habitats through human activities. Furthermore, many seahorses are caught accidentally (as bycatch) in fishing nets, particularly in trawl nets intended to catch shrimps.

The following countries and territories are known to have traded seahorses sometime between 1996 and now:

Africa: Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Egypt, Gambia, Guinea, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo

Asia: Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Republic of, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Macau, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan (province of China), Thailand, Vietnam

Europe: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, United Kingdom

Middle East: Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates

North and Central America and the Caribbean: Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Guam, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, USA

South America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela

Oceania: Australia, Fiji, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu

The largest exporter of seahorses appears to be Thailand, followed by Guinea and Senegal. Most dead seahorses are probably imported to mainland China, Taiwan (Province of China) and Hong Kong SAR, while the U.S.A. is the largest reported importer of live seahorses.

TCM has made use of the seahorse for more than 600 years. Seahorses and their relatives, the pipefish, are used to treat a variety of illnesses, from asthma and arteriosclerosis, to incontinence and impotence. They also provide remedies for skin ailments, high cholesterol levels, excess throat phlegm, goiters, heart disease, and lymph node disorders. As medicines and food are considered to lie along a continuum in Chinese culture, a large number of seahorses are eaten as tonic foods.

TCM is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a valid form of health care, has been codified for at least 2000 years, and is trusted by a quarter of the world’s population. It is important to focus on the over-consumption of seahorses, rather than the validity of TCM treatments. For example, it may be possible for practitioners and consumers to adjust the consumption of seahorses to relieve pressure on certain species and size classes.